“We think this is extremely crucial…[but there are] a lot of old bulls in both parties who just don’t want to do it.” Speaking of which, paging Tommy Carcetti…Finding it’s harder to shake out the old system than anticipated, the incoming Dems are already backing away from a key 9/11 panel suggestion, one that would centralize congressional oversight and funding of intelligence matters in the intelligence subcommittee (to be chaired by Reyes, a.k.a. not-Hastings/Harman) at the expense of the armed services and appropriations defense subcommittees (the latter of which will be chaired by also-ran Murtha.) “Democratic leadership dust-ups this month severely limited the ability of House Speaker-elect Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) to implement the commission’s recommendations, according to Democratic aides.“

Category: 9/11

9/11/06.

The Strength of Collective Man.

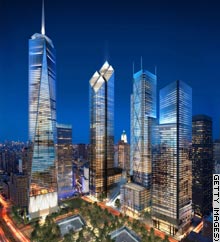

“When you look at this tower, it will immediately tell you where the memorial park is. It’s always pointing.” Architects and developers reveal the rest of the proposed Lower Manhattan skyline at Ground Zero, to accompany the Freedom Tower.

Just another day in Lower Manhattan.

As the five-year anniversary approaches, New York Magazine wonders “What if 9/11 never happened?”, putting the question to Andrew Sullivan, Thomas Friedman, Dahlia Lithwick, Frank Rich, Tom Wolfe, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Fareed Zakaria, Douglas Brinkley, and others. (By way of Lots of Co.)

Towers of Stone.

If you’re going to see only one movie about 9/11, see Paul Greengrass’ United 93, far and away the best movie of the year. If you’re going to see two movies about 9/11, see United 93 and Spike Lee’s The 25th Hour, still the best film I’ve seen about the day’s aftermath here in Gotham. And, if you’re going to see three movies about 9/11…hmm, now that’s a tough one. Maybe add the first hour of Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds and the first half-hour of Oliver Stone’s surprisingly rote World Trade Center? While much better than the godawful Alexander or the misfiring Any Given Sunday, World Trade Center nevertheless suggests that Stone is still somewhat off his game. The movie has some moments of genuine power, particularly in its first act (as it would have to given the potency of its source material), but it’s hard to believe the director of JFK, Platoon, Natural Born Killers, and Nixon would make such a staid and conventional Lifetime movie-of-the-week from the defining tragedy of our decade. (Even more unStonelike, aside from an indirect dig at the blathering television newsmedia, who continuously recycle the morning’s events well past everyone’s endurance, WTC is also resolutely apolitical and uncontroversial.) In sum, World Trade Center is crisply-made and at times affecting, but nowhere near as interesting or eventful a movie as you might expect. As EW’s Owen Gleiberman aptly summed it up, “World Trade Center isn’t a great Stone film; it’s more like a decent Ron Howard film.“

If you’re going to see only one movie about 9/11, see Paul Greengrass’ United 93, far and away the best movie of the year. If you’re going to see two movies about 9/11, see United 93 and Spike Lee’s The 25th Hour, still the best film I’ve seen about the day’s aftermath here in Gotham. And, if you’re going to see three movies about 9/11…hmm, now that’s a tough one. Maybe add the first hour of Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds and the first half-hour of Oliver Stone’s surprisingly rote World Trade Center? While much better than the godawful Alexander or the misfiring Any Given Sunday, World Trade Center nevertheless suggests that Stone is still somewhat off his game. The movie has some moments of genuine power, particularly in its first act (as it would have to given the potency of its source material), but it’s hard to believe the director of JFK, Platoon, Natural Born Killers, and Nixon would make such a staid and conventional Lifetime movie-of-the-week from the defining tragedy of our decade. (Even more unStonelike, aside from an indirect dig at the blathering television newsmedia, who continuously recycle the morning’s events well past everyone’s endurance, WTC is also resolutely apolitical and uncontroversial.) In sum, World Trade Center is crisply-made and at times affecting, but nowhere near as interesting or eventful a movie as you might expect. As EW’s Owen Gleiberman aptly summed it up, “World Trade Center isn’t a great Stone film; it’s more like a decent Ron Howard film.“

Much like United 93, World Trade Center begins in the wee morning hours of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 (3:29 am, to be exact), as some of New York City’s earliest risers — and, indeed, the City itself — wake up to face another day. Among the bleary-eyed morning commuters are two of the Port Authority’s finest, family men Sgt. John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and rookie officer Will Jimeno (Michael Pena). We follow McLoughlin and Jimeno through the beginnings of their usual routine — walking the beat at the Port Authority bus terminal — until the shadow of a jet zooms overhead, and the horrors of the day start to unfold. An expert on the World Trade Center since before the 1993 bombing, McLoughlin quickly leads a busload of anxious Port Authority cops down to what will soon become known as Ground Zero, where he and a small team (including Jimeno), after choking back their awe and fear, enter the mall concourse between the towers. As metal coughs, creaks, and grinds onimously in the background, these first responders gather up their gear and prepare for their trek up Tower 1. But, just when McLoughlin gets wind that there may be something wrong in Tower 2 (news which Jimeno heard on the way down), a terrible Wrath-of-God rumbling begins, and the World caves in. Having barely made a desperate sprint to the elevator shaft, which McLoughlin — thankfully — had known was the strongest part of the building, the surviving members of his team find themselves entombed (and partially crushed) amid a hellish morass of concrete and twisted steel. Then — although they have no clue what’s going on — the other Tower falls, and McLoughlin and Jimeno are left alone in the dark, hopelessly pinned underneath the smoldering wreckage of the two towers.

Much like United 93, World Trade Center begins in the wee morning hours of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 (3:29 am, to be exact), as some of New York City’s earliest risers — and, indeed, the City itself — wake up to face another day. Among the bleary-eyed morning commuters are two of the Port Authority’s finest, family men Sgt. John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and rookie officer Will Jimeno (Michael Pena). We follow McLoughlin and Jimeno through the beginnings of their usual routine — walking the beat at the Port Authority bus terminal — until the shadow of a jet zooms overhead, and the horrors of the day start to unfold. An expert on the World Trade Center since before the 1993 bombing, McLoughlin quickly leads a busload of anxious Port Authority cops down to what will soon become known as Ground Zero, where he and a small team (including Jimeno), after choking back their awe and fear, enter the mall concourse between the towers. As metal coughs, creaks, and grinds onimously in the background, these first responders gather up their gear and prepare for their trek up Tower 1. But, just when McLoughlin gets wind that there may be something wrong in Tower 2 (news which Jimeno heard on the way down), a terrible Wrath-of-God rumbling begins, and the World caves in. Having barely made a desperate sprint to the elevator shaft, which McLoughlin — thankfully — had known was the strongest part of the building, the surviving members of his team find themselves entombed (and partially crushed) amid a hellish morass of concrete and twisted steel. Then — although they have no clue what’s going on — the other Tower falls, and McLoughlin and Jimeno are left alone in the dark, hopelessly pinned underneath the smoldering wreckage of the two towers.

Up to this point, Stone’s movie is almost completely riveting, and the scenes in the doomed (and painstakingly recreated) WTC concourse in particular have a horrifying “I can’t believe I’m seeing this” feel to them…Unfortunately, we’re only about thirty minutes into the film. For the next ninety minutes, WTC switches back and forth between these two dying peace officers and the anxious pacing of their confused and griefsick wives, Donna McLoughlin (Maria Bello, wearing really distracting blue contacts that make her look Fremen) and a pregnant Allison Jimeno (Maggie Gyllenhaal). Alas, horror yields to hokum, and the film pretty much wallows in melodramatic platitudes for the remainder of its run. This is not to say that the rest of World Trade Center is terrible — It’s competently made and, given the human drama at stake here, even moving at times. But it’s also breathtakingly conventional, with Stone (and WTC‘s writer Andrea Berloff) pulling every single disaster-movie-tearjerker cliche out of the book by the end: flashbacks to happier times, ghostly visions of loved ones (as well as a faceless Jesus, which is the closest Stone gets to his usual obligatory shaman cameo), the kid who won’t accept the situation at face value, the musing over last words spoken, etc. (The bromides also extend to the brief and not very realistic characterizations of some of the post-collapse rescuers, which include Stephen Dorff, Frank Whaley, and Michael Shannon.)

Up to this point, Stone’s movie is almost completely riveting, and the scenes in the doomed (and painstakingly recreated) WTC concourse in particular have a horrifying “I can’t believe I’m seeing this” feel to them…Unfortunately, we’re only about thirty minutes into the film. For the next ninety minutes, WTC switches back and forth between these two dying peace officers and the anxious pacing of their confused and griefsick wives, Donna McLoughlin (Maria Bello, wearing really distracting blue contacts that make her look Fremen) and a pregnant Allison Jimeno (Maggie Gyllenhaal). Alas, horror yields to hokum, and the film pretty much wallows in melodramatic platitudes for the remainder of its run. This is not to say that the rest of World Trade Center is terrible — It’s competently made and, given the human drama at stake here, even moving at times. But it’s also breathtakingly conventional, with Stone (and WTC‘s writer Andrea Berloff) pulling every single disaster-movie-tearjerker cliche out of the book by the end: flashbacks to happier times, ghostly visions of loved ones (as well as a faceless Jesus, which is the closest Stone gets to his usual obligatory shaman cameo), the kid who won’t accept the situation at face value, the musing over last words spoken, etc. (The bromides also extend to the brief and not very realistic characterizations of some of the post-collapse rescuers, which include Stephen Dorff, Frank Whaley, and Michael Shannon.)

Along those lines, I don’t want to make it sound like I’m criticizing the true story of McLoughlin and Jimeno — their story is a miracle, and one of the few small beacons of cheer from that terrible morning. But, when a movie called World Trade Center ends up focusing so narrowly on these two survivors and — big spoiler, but it’s in the poster — ends with happy reunions and two families getting unexpectedly wonderful news, something seems off. Unlike United 93 which managed to recapture both the primal nightmare and unexpected heroism of that day and did so unblinkingly, without sugar-coating the fate of the fallen, WTC instead transmutes the stark emotions of 9/11 into saccharine, easy-to-swallow caplets of Hollywood sentiment. Some people may like this alchemy better, I suppose, but, in all honesty, to me it felt like an overly-sanitized cop-out (or two cops-out, in this case.) World Trade Center means well and is a decent film in every sense of the word. But the first half-hour notwithstanding, it also feels superfluous — which, given the confluence of director and material here, is somewhat surprising.

Along those lines, I don’t want to make it sound like I’m criticizing the true story of McLoughlin and Jimeno — their story is a miracle, and one of the few small beacons of cheer from that terrible morning. But, when a movie called World Trade Center ends up focusing so narrowly on these two survivors and — big spoiler, but it’s in the poster — ends with happy reunions and two families getting unexpectedly wonderful news, something seems off. Unlike United 93 which managed to recapture both the primal nightmare and unexpected heroism of that day and did so unblinkingly, without sugar-coating the fate of the fallen, WTC instead transmutes the stark emotions of 9/11 into saccharine, easy-to-swallow caplets of Hollywood sentiment. Some people may like this alchemy better, I suppose, but, in all honesty, to me it felt like an overly-sanitized cop-out (or two cops-out, in this case.) World Trade Center means well and is a decent film in every sense of the word. But the first half-hour notwithstanding, it also feels superfluous — which, given the confluence of director and material here, is somewhat surprising.

Spirit of 93.

Whether or not the world really needed a film about the events that took place on United Flight 93 the morning of September 11, 2001 is, I suppose, still an open question. I can see both sides of the argument: that it’s too soon for a movie about 9/11 and that our current involvement in the war on terror demands we come to terms with what happened that day. (As my father pointed out, the WWII generation saw plenty of war flicks come out while the conflict still raged in Europe and the Pacific.) For my own part, even despite the stellar reviews for Paul Greengrass’ film, it took me a few weeks to crank up the nerve to sit through a movie that I figured would be at best chilling and heart-rending and at worst deeply exploitative and repellent. That being said, having run the gauntlet earlier this week, I can now happily report that United 93 is magnificent, and arguably the best possible film that could’ve been made about this story. Both harrowing and humane, it’s the movie of the year so far.

Whether or not the world really needed a film about the events that took place on United Flight 93 the morning of September 11, 2001 is, I suppose, still an open question. I can see both sides of the argument: that it’s too soon for a movie about 9/11 and that our current involvement in the war on terror demands we come to terms with what happened that day. (As my father pointed out, the WWII generation saw plenty of war flicks come out while the conflict still raged in Europe and the Pacific.) For my own part, even despite the stellar reviews for Paul Greengrass’ film, it took me a few weeks to crank up the nerve to sit through a movie that I figured would be at best chilling and heart-rending and at worst deeply exploitative and repellent. That being said, having run the gauntlet earlier this week, I can now happily report that United 93 is magnificent, and arguably the best possible film that could’ve been made about this story. Both harrowing and humane, it’s the movie of the year so far.

United 93, like 9/11, begins like any other day. For most of the first third of the film (the opening scenes, where we watch the four terrorists make their final prayers and preparations, notwithstanding) we simply follow people beginning their work day: air traffic controllers look at the weather and discuss possible delays, pilots make small-talk on their way to the cockpit, flight attendants prepare the cabin, and sleepy, anonymous passengers sit around Newark airport, making phone calls or waiting with blank, thousand-yard-stares for their turn to board. It looks exactly like every single airport terminal you’ve ever seen, and, if you had no sense of what’s to come next, you might be deadly bored by all this reveling in mundanity. But, there’s a method to Greengrass’s madness — not only do these early scenes root the film in our world (as well as foster some sickening suspense — we’re obviously waiting for the other shoe to drop), but they take us back to what Karl Rove might call a “pre-9/11 mentality.”

It’s no small testament to the film’s intricate set-up that, when quintessentially Bostonian and New Yorker ATC guys start noticing some planes acting quirky, we sense their palpable confusion even though we know exactly what’s going on, and — when the second plane hits the World Trade Center (which is never shown, except on CNN or in long shots from the Newark control tower) — we feel as shocked as they do, all over again. From there, the film’s second act involves civilian and military air traffic officials (some of whom are played by the real people involved) struggling to make sense of a increasingly horrifying situation for which everyone was totally unprepared. ATC men feverishly watch the wrong planes for signs of a hijacking, FAA authorities put together a board of possible suspect flights and try to track down an AWOL military attache for some answers, a plane that was thought destroyed pops up again on the radar dangerously close to Washington, unarmed fighters (the best anyone could find on short notice) scramble in the wrong direction over the ocean, and NORAD waits desperately for the presidential authorization to fire on hijacked airliners, to no avail. (Think My Pet Goat.)

And, in the meantime, United 93 begins its own hellish journey, as the four terrorists on that plane (who, to Greengrass’ credit, are portrayed as multifaceted as they could be, given their vile plan), after some silent soul-searching, spring into action: They take over the cockpit, scare into submission the passengers (all of whom are played by relative unknowns, although some — such as David Rasche of Sledge Hammer — look vaguely familiar), and set a course for the Capitol. Thrust to the back of the plane by a “bomb”-carrying hijacker, having little-to-no sense of what’s going on in the cockpit, and wracked with fear, grief, and confusion, the passengers of United 93 — operating with even less knowledge than the people on the ground — eventually piece enough to discover that they must act. This all takes place in real time, and isn’t played as cheap film heroics in the slightest. Like everything else in United 93, it all feels terrifyingly real, making the passengers’ final, collective, desperate lunge for survival one of the most visceral and cathartic movie sequences in years — it, like the final shot, will linger in your memory for days to come.

And, in the meantime, United 93 begins its own hellish journey, as the four terrorists on that plane (who, to Greengrass’ credit, are portrayed as multifaceted as they could be, given their vile plan), after some silent soul-searching, spring into action: They take over the cockpit, scare into submission the passengers (all of whom are played by relative unknowns, although some — such as David Rasche of Sledge Hammer — look vaguely familiar), and set a course for the Capitol. Thrust to the back of the plane by a “bomb”-carrying hijacker, having little-to-no sense of what’s going on in the cockpit, and wracked with fear, grief, and confusion, the passengers of United 93 — operating with even less knowledge than the people on the ground — eventually piece enough to discover that they must act. This all takes place in real time, and isn’t played as cheap film heroics in the slightest. Like everything else in United 93, it all feels terrifyingly real, making the passengers’ final, collective, desperate lunge for survival one of the most visceral and cathartic movie sequences in years — it, like the final shot, will linger in your memory for days to come.

In short, United 93 is undeniably hard to watch at times, and I can see why many folks out there would steer clear of it like the plague. Still, if you feel like you can handle the subject matter, United 93 is a must-see film. While it doesn’t even really attempt to offer a broader perspective on the events of 9/11, it’s hard to imagine a movie that could reconstruct the emotional experience of that day as faithfully and without cynicism or exploitation as this one.

Blood from a Stone.

I’m way behind on my movies (although I made some headway today — more soon) and still haven’t caught United 93 yet…Nevertheless, the trailer for Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center is now online. Hm. This looks exploitative as all-git-out, and, while Conan and Nixon will always get him points, Stone has lost major cred with me after Any Given Sunday and the atrocious Alexander. I’ll probably miss it.

Ground Zero Hour.

“With today’s agreement, we can now move forward with rebuilding the World Trade Center.” After months of wrangling, developer Larry Silverstein and the Port Authority strike a deal on the planned “Freedom Tower” at the WTC site. Said Pataki: ““This is the last stumbling block to putting shovels in the ground.” Construction on the 1776-foot Freedom Tower is set to be completed by 2012.

Snakes on a Plane.

The new trailer for United 93 is now online. This idea of this film feels really unnecessary and verges on exploitative…but, as I said with the teaser, Paul Greengrass is a pretty darned good director, so I’m still curious to see what he makes of it.

Fight Club.

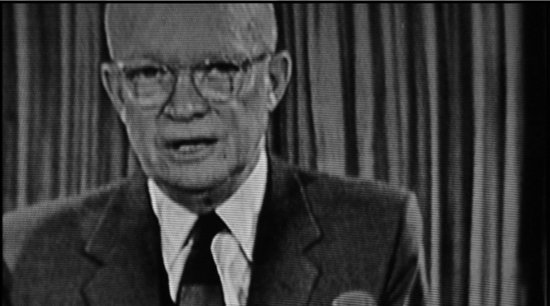

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes.” That flaming liberal Dwight Eisenhower’s somber farewell address to the nation is the historical and thematic anchor for Eugene Jarecki’s documentary Why We Fight, a sobering disquisition on American militarism and foreign policy since 9/11. In essence, Why We Fight is the movie Fahrenheit 9/11 should have been. Like F911, this film preaches to the choir, but it also makes a more substantive critique of Dubya diplomacy and the 9/11-Iraq switcheroo, with much less of the grandstanding that marred Moore’s earlier documentary (and drove right-wing audiences berzerk.)

Sadly, the basic tale here is all-too-familiar by now. Ensconced in Dubya’s administration from the word go, the right-wing think-tank crowd (Wolfowitz, Perle, Kristol, etc.) used the tragedy of 9/11 as a pretext to enact all their neocon fantasies (spelled out in this 2000 Project for a New American Century report), beginning in Iraq. Taken into consideration with Cheney the Military-Contractor-in-Chief doling out fat deals to his Halliburton-KBR cronies from the Vice-President’s office, and members of Congress meekly signing off on every military funding bill that comes down the pike (partly because, as the film points out, weapons systems such as the B-1 or F-22 have a part built in every state), it seems uncomfortably clear that President Eisenhower’s grim vision has come to pass.

To help him rake this muck, Jarecki shrewdly gives face-time not only to learned critics of recent foreign-policy — CIA vet Chalmers Johnson, Gore Vidal (looking unwell) — but also to the neocons themselves. Richard Perle is here, saying (as always) insufferably self-serving things, and Bill Kristol glows like a kid in a candy store when he gets to talk up his role in fostering Dubya diplomacy. (Karen Kwiatkowski, a career military woman who watched the neocon coup unfold within the corridors of the Pentagon, also delivers some keen insights.) And, when discussing the corruption that festers in the heart of our Capitol, Jarecki brings out not only Charles Lewis of the Center for Public Integrity but that flickering mirage of independent-minded Republicanism, John McCain. (In fact, Jarecki encapsulates the frustrating problem with McCain in one small moment: Right after admitting to the camera that Cheney’s no-bid KBR deals “look bad”, the Senator happens to get a call from the Vice-President. In his speak-of-the-devil grimace of bemused worry, you can see him mentally falling into line behind the administration, as always.)

To be sure, Why We Fight has some problems. There’s a central tension in the film between the argument that Team Dubya is a corrupt administration of historical proportions and the notion that every president since Kennedy has been party to an increasingly corrupt system, and it’s never really resolved satisfactorily here. Jarecki wants you to think that this documentary is about the rise of the Imperial Presidency across five decades, but, some lip service to Tonkin notwithstanding, the argument here is grounded almost totally in the Age of Dubya. (I don’t think it’s a bad thing, necessarily, but it is the case.) And, sometimes the critique seems a little scattershot — Jarecki seems to fault the Pentagon both for KBR’s no-bid contracts and, when we see Lockheed and McDonnell-Douglas salesmen going head-to-head, for bidding on contracts. (Still, his larger point is valid — As Chalmers Johnson puts it, “When war becomes that profitable, you’re going to see more of it.“)

Also, the film loses focus at times and meanders along tangents — such as the remembrances of two Stealth Fighter pilots on the First Shot Fired in the Iraq war, or the glum story of an army recruit in Manhattan looking to turn his life around. This latter tale, along with the story of Wilton Sekzer, a retired Vietnam Vet and NYPD sergeant who lost his son on 9/11 and wants somebody to pay, are handled with more grace and less showmanship than similar vignettes in Michael Moore’s film, but they’re in the same ballpark. (As an aside, I was also somewhat irked by shots of NASA thrown in with the many images of missile tests and ordnance factories. Ok, both involve rockets, research, and billions of dollars, but space exploration and war are different enough goals that such a comparison merits more unpacking.)

Nevertheless, Why We Fight is well worth-seeing, and hopefully, this film will make it out to the multiplexes. If nothing else, it’ll do this country good to ponder anew both a president’s warning about the “disastrous rise of misplaced power,” and a vice-president’s assurance that we’ll be “greeted as liberators.”

.jpg)