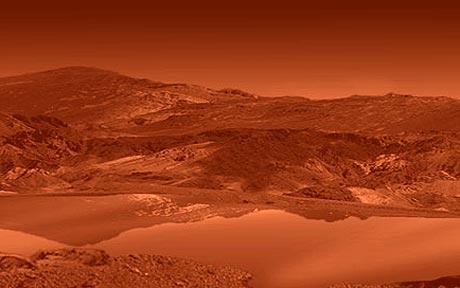

“Our findings are a reminder that life as we know it could be much more flexible than we generally assume or can imagine,” Felisa Wolfe-Simon, an astrobiology researcher at the U.S. Geological Survey, said.“

Whoa. NASA announces it has discovered a strange new bacteria in California’s Mono Lake that use arsenic instead of phosphorus, previously considered indispensable to life. “It gets in there and sort of gums up the works of our biochemical machinery,’ ASU’s Ariel Anbar, a co-author of the Science paper, explained.

Big doings? Definitely — The existence of these viable microbes suggests new biochemical possibilities for life on distant (or even not-so-distant) planets. But Discover‘s Ed Yong advises caution: “The discovery is amazing, but it’s easy to go overboard with it…For a start, the bacteria – a strain known as GFAJ-1 – don’t depend on arsenic. They still contain detectable levels of phosphorus in their molecules and they actually grow better on phosphorus if given the chance. It’s just that they might be able to do without this typically essential element – an extreme and impressive ability in itself.“

Update: “As soon as Redfield started to read the paper, she was shocked. ‘I was outraged at how bad the science was,’ she told me.” Hold the champagne: Slate‘s Carl Zimmer surveys the scientific pushback, and it is considerable. “‘[N]one of the arguments are very convincing on their own.’ That was about as positive as the critics could get. ‘This paper should not have been published,’ said Shelley Copley of the University of Colorado.”