“This time, the FWP could begin by documenting the ground-level impact of the Great Recession; chronicling the transition to a green economy; or capturing the experiences of the thousands of immigrants who are changing the American complexion. Like the original FWP, the new version would focus in particular on those segments of society largely ignored by commercial and even public media.” In the wake of the turmoil engulfing the newspaper industry at the moment (see also: The Wire, Season 5), journalist Mark Pinsky argues in TNR for a 21st century revival of the Federal Writers’ Project. Given the woeful state of the academic job market during this current downturn, I bet there are quite a few historians out there who’d give this a “Huzzah!”

Category: Ivory Tower

WP: Beware the Brain Trust.

“While Obama’s picks have been lauded for their ethnic and ideological mix, they lack diversity in one regard: They are almost exclusively products of the nation’s elite institutions and generally share a more intellectual outlook than is often the norm in government.” Yikes! Apparently delving deep for ways to stir up trouble, the WP raises an eyebrow at the purported braininess of the Obama cabinet. “They are really smart people, but they will never take an obvious solution if they can think of an ingenious one. They’re all too clever by half…These degrees confer knowledge but not judgment. Their heads are on grander themes…and they’ll trip on obstacles on the ground.“

Hmmm…I dunno. After several years in academia, I’m well aware of the ways in which really smart, intellectual-minded people can end up overthinking a problem. But, particularly after the last eight years, choosing brainy folk as a Cabinet-filling strategy still sounds a heck of a lot better to me than the alternative.

Of Fact and Fiction.

“Historians and novelists are kin, in other words, but they’re more like brothers who throw food at each other than like sisters who borrow each other’s clothes. The literary genre that became known as ‘the novel’ was born in the eighteenth century. History, the empirical sort based on archival research and practiced in universities, anyway, was born at much the same time. Its novelty is not as often remembered, though, not least because it wasn’t called ‘novel.’ In a way, history is the anti-novel, the novel’s twin, though which is Cain and which is Abel depends on your point of view.” By way of The Late Adopter, historian Jill Lepore surveys the origins of — and often-thorny relation between — history and the novel.

Wilentz Jumps the Shark.

“The Obama campaign has yet to reach bottom in its race-baiter accusations…They promise to continue until they win the nomination, by any means necessary.” Taylor Marsh, Ph.D? A Clinton supporter from Day One, he at first dismissed Obama as merely the newest in a long tradition of “beautiful losers,” like Adlai Stevenson and Bill Bradley. (If you come ’round here often, you can probably guess that didn’t sit too well with me. In fact, it’s basically the same argument recently made by friend and colleague David Greenberg, before he went the way of the Great White Hope.) Well, if today’s TNR piece is any indication, historian Sean Wilentz only knows how to lose ugly. Despite the fact that Wilentz has been ranting worse than Krugman for most of this election cycle, I’ve been inclined to give him a pass, partly as a professional courtesy of sorts to a well-esteemed historian of whom I once thought quite highly, and partly because of his well-publicized Dylan fandom. Well, no more. Wilentz has been writing increasingly blatant pro-Clinton spin pieces throughout the campaign, which is his wont as a Clinton supporter, I suppose. But here he’s penned a shrill and intemperate screed which, frankly, is more embarrassing than anything else. It’s the type of angry, weirdly conspiratorial rant you’d expect to be written by an anonymous, and possibly drunk, Salon poster, not one of the more venerable American historians in the profession.

“The Obama campaign has yet to reach bottom in its race-baiter accusations…They promise to continue until they win the nomination, by any means necessary.” Taylor Marsh, Ph.D? A Clinton supporter from Day One, he at first dismissed Obama as merely the newest in a long tradition of “beautiful losers,” like Adlai Stevenson and Bill Bradley. (If you come ’round here often, you can probably guess that didn’t sit too well with me. In fact, it’s basically the same argument recently made by friend and colleague David Greenberg, before he went the way of the Great White Hope.) Well, if today’s TNR piece is any indication, historian Sean Wilentz only knows how to lose ugly. Despite the fact that Wilentz has been ranting worse than Krugman for most of this election cycle, I’ve been inclined to give him a pass, partly as a professional courtesy of sorts to a well-esteemed historian of whom I once thought quite highly, and partly because of his well-publicized Dylan fandom. Well, no more. Wilentz has been writing increasingly blatant pro-Clinton spin pieces throughout the campaign, which is his wont as a Clinton supporter, I suppose. But here he’s penned a shrill and intemperate screed which, frankly, is more embarrassing than anything else. It’s the type of angry, weirdly conspiratorial rant you’d expect to be written by an anonymous, and possibly drunk, Salon poster, not one of the more venerable American historians in the profession.

Am I overstating the case? Well, let’s take a look at some of the spleen-venting on display here: “After several weeks of swooning, news reports are finally being filed about the gap between Senator Barack Obama’s promises of a pure, soul-cleansing ‘new’ politics and the calculated, deeply dishonest conduct of his actually-existing campaign. But it remains to be seen whether the latest ploy by the Obama camp–over allegations about the circulation of a photograph of Obama in ceremonial Somali dress–will be exposed by the press as the manipulative illusion that it is.” Calculated, deeply dishonest conduct? Ploy? Manipulative illusion? Tell us what you really think, Prof. Wilentz.

And that’s just the first paragraph. It gets worse. Check out this unsightly sentence: “As insidious as these tactics are, though, the Obama campaign’s most effective gambits have been far more egregious and dangerous than the hypocritical deployment of deceptive and disingenuous attack ads.” Riiight. I really started to buy your case after that fifth negative adjective or so.

I’d spend time refuting Wilentz point for point if I thought he was trying to make a reasonable case here. But he spends most of the article just shrieking “race baiter race baiter race baiter!“, punctuated with occasional whiny, Clintonesque accusations of pro-Obama media bias. (One of the many targets of Wilentz’s wrath, Frank Rich, has recently pointed out the problems with that line of argument.) But, in general terms, in order to buy what Wilentz is selling here, you’d have to believe all of the following:

And so on. Meanwhile, in between the purging of bile (Obama’s “cutthroat, fraudulent politics,” “the most outrageous deployment of racial politics since Willie Horton, “the most insidious” since Reagan in Philadelphia), Wilentz trots out stale and rather sad race-conspiracy talking points from pro-Clinton hives like TalkLeft, such as Jesse Jackson Jr. chiding superdelegate Emanuel Cleaver for standing in the way of a black president. (Please. As if female superdelegates weren’t receiving similar calls from the Clinton camp. Clinton even made the explicit gender case — again — in the debate tonight.) I dunno, perhaps this is what you should expect from a thinker who cites Philip Roth as an expert on black-white relations. (Although, fwiw, Roth’s voting Obama.) Nevertheless, Wilentz has crossed over the line here from politically-minded historian to unhinged demagogue, and made himself to look absolutely ridiculous in the process. It’ll be hard to read his historical work in the future without this hyperbolic and ill-conceived polemic in mind.

Alma Mater’s Alright.

“Obama represents an opportunity for a Democratic nominee who represents the value of service, intelligence, and judgment, and, most of all, an opportunity for real change, unburdened by favors owed and ideals lost. He deserves your vote.” The Harvard Crimson endorses Barack Obama — on the issues.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner.

“For those who attempt it, the doctoral dissertation can loom on the horizon like Everest, gleaming invitingly as a challenge but often turning into a masochistic exercise once the ascent is begun. The average student takes 8.2 years to get a Ph.D.; in education, that figure surpasses 13 years. Fifty percent of students drop out along the way, with dissertations the major stumbling block. At commencement, the typical doctoral holder is 33, an age when peers are well along in their professions, and 12 percent of graduates are saddled with more than $50,000 in debt.”

By way of Little Bit Left, a new site by a Columbia colleague that’s well worth adding to the blogroll, the NYT surveys the sad plight of the modern ABD. (I’ll be 33 at my current expected finish date, seven years after starting, and my cohort’s attrition rate has been significant, so it seems the stats bear out in my case.) “Those who insist on dissertations are aware that they must reduce the loneliness that defeats so many scholars…’It’s easy, especially in our field, to feel isolated, and that tends to slow people down…There’s no sense of belonging to an academic community.‘” Oh, I dunno…Berk and I often have very scintillating conversations…progressive citizenship, New Era consumerism, socks, squirrels, you name it.

Ahmadinejad in the Lions’ Den.

So, you’ll never guess who came to campus today…It didn’t get much press or anything, but Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad kicked off his NY tour this morning by being eviscerated in public by Columbia’s president, Lee Bollinger. Normally, I’d say it’s poor form to hijack an invited speaker like that, but: the national temper is running angry, Ahmadinejad’s no angel by any means, and — most importantly — the questions Bollinger posed demand substantive answers. (Besides, a furor is what Ahmadinejad wanted anyway.)

All that being said, I still think it was a dumb political stunt (on both ends) to disinvite the Iranian president from visiting Ground Zero. A couple of points people seem to have forgotten lately: 1. Iran didn’t have anything to do with 9/11, and 2. Whatever’s going on on the Iraqi border, we’re not currently at war with them. Most importantly, why wouldn’t we want a man who’s trying to obtain nukes to see the lasting consequences of a large-scale atrocity firsthand? If the sight of that still-gaping wound in the heart of the city gave him pause for even a moment, the world would be better for it.

War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.

“Faust’s interpretation helps explain the way the US responded to the 9-11 terrorist attacks with a war on Iraq. ‘Even a war against an enemy who had no relationship to September 11’s terrorist acts would do,’ she notes. People supported war not just because of the rational arguments offered by the White House, but also ‘because the nation required the sense of meaning, intention, and goal-directedness, the lure of efficacy that war promises.’ It was especially necessary to restore a sense of control after the terrorism of 9-11 had ‘obliterated’ it. The US, she concludes, ‘needed the sense of agency that operates within the structure of narrative provided by war.’” In the pages of The Nation, Jon Wiener evaluates new Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust’s work on war mania.

Mother of Invention.

10,000 Men of Harvard…and one woman leading the charge: According to the Crimson, author and historian Drew Gilpin Faust is set to become Larry Summers’ replacement as president of Harvard, and the first female president of dear alma mater in 371 years. She’s already an improvement on Summers just by showing up.

Muddled in their Intent.

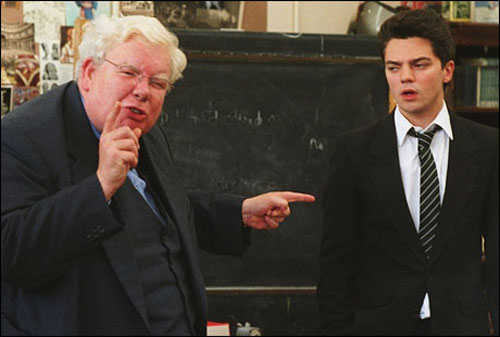

I never caught the source material while it was on Broadway, so I can’t compare it to the play. But, while I found Nicholas Hytner’s film of Alan Bennett’s The History Boys to be a thoughtful and decently engaging piece of work, it makes for a somewhat unnatural and theatrical evening of cinema. The ideas in (the) play are obviously intriguing and worthy of contemplation, but — with several performances better suited for the back rows than the big screen (most notably Clive Merrison as a schoolmaster out of Monty Python) and a gaggle of bon mot-spouting teenagers that, at least in my own personal and teaching experience, act in no way at all like teenagers — The History Boys often felt forced to me. It’s a worthy piece of pedagogy, I suppose, and I’m almost positive it must work better on Broadway. But, overall, I thought it trafficked in archetypes more than it does in real-world, flesh-and-blood characters — more fiction than history, I’d say — and this close to the action, its faults are harder to hide.

As iconic cuts by New Order and The Smiths tip off in the opening moments, The History Boys takes place in the early 1980’s — 1983 Sheffield, to be exact. But don’t let “Blue Monday” and “This Charming Man” fool you: our story in fact takes place in a boys’ preparatory school, one — references to W.H. Auden and Brief Encounter notwithstanding — seemingly hermetically sealed from the outside world at large. Here in this academic biodome, several young lads, having done exceedingly well on their A-levels, now prep for the grueling college application process, in the particular hopes of getting into Oxford and Cambridge.

To aid them in this arduous process are two history professors dueling for their impressionable minds…and bodies: In the relativist corner, Professor Irwin (Stephen Campbell Moore), a sharp, young, and assured (if closeted) new hiree dedicated to promoting the ironies and contingencies of history. Meanwhile, over in the knowledge-for-its-own-sake department rests Professor Hector (Richard Griffiths, the soul of the film.) Orwell looming over his shoulder (the two agree on the debasement of “worrrrds“), Hector is a grotesque but endearing fellow who one might call avuncular, were it not for his rather unfortunate penchant for fondling his students’ genitals. Shrugging off these occasional gropes (far more sanguinely than seems realistic, IMHO), the history boys perform poetry, film scenes, and cabaret tunes for the latter and develop streaks of contrarian skepticism for the former, all the while learning a thing or two not only about life and history, but of the Achilles’ Heels of their esteemed teachers.

In a nutshell, the basic problem I had with The History Boys is this: A decade ago, a friend of mine once described a mutual acquaintance as “the ideal twenty-two-year-old…in the eyes of a fifty-five-year old.” Well, this movie’s got a whole pack of ’em. All of the young actors here are decent enough — if a bit broad, cinematically speaking — with Samuel Barnett (as Posner, a boy trapped in the very special hell that is an unrequited teenage crush) and Dominic Cooper (as Dakin, a young man increasingly hopped up on Nietzsche and the power of his own burgeoning sexuality) given the most to do. But, as they effortlessly spin forth witticisms at the most opportune moments and gather around the piano without even a trace of cynicism or irony (“the shackles of youth,” as the line goes) about them, they all seemed very, very improbable to me…and that’s even notwithstanding their handling of the aforementioned sexual misdeeds. (Full disclosure: I have much the same problem with Whit Stillman films.)

Yet, once you take it as inherently fanciful and somewhat missuited for the big screen, there are still elements to enjoy in Boys, including a number of thoughtful disquisitions on the uses and practices of history as a discipline: for example, on contingency, commemoration, and the rise of a more gender-balanced understanding of the past (the latter memorably delivered by Frances De La Tour, who, while excellent here as a jaded prof, still unfortunately kept reminding me of Madame Maxime.) Admittedly, these digressions do seem shoehorned in at times — and brought back memories of fading historiography seminars — but they still offer some keen grist for the philosophical mill. (That being said, I somehow suspect that the teaching of history is a less sexually charged discipline than as seen here, where it’s rife with more suppressed longing than the Catholic priesthood. But perhaps I haven’t been at it long enough.)