As most everyone keeping up on current events these days knows, the people around the president, as well as the president himself, spend a good bit of time

emphasizing the pragmatic nature of this administration. One senior administration official recently deemed the president a

“devout nonideologue”, and Obama himself has argued several times that he aims to tackle the myriad problems before us with a “ruthless pragmatism.” Now, we’ve seen nothing to indicate that Obama’s pragmatic nature is an act. If anything, from installing Sen. Clinton as his Secretary of State to keeping Sec. Gates at Defense, it’s clear that pragmatism, accommodation, and inclusiveness are his temperamental instincts as a politician. Nevertheless, it’s also clear that comparisons to Franklin Roosevelt, and

the “bold, persistent experimentation” Roosevelt promised in 1932 — and subsequently followed through on over the course of the decade — aren’t entirely undesired by the White House.

Well, I’ve been traveling over the past few days, and thus haven’t been following the news as closely as usual. Still, even given President Obama’s health care announcement on Monday (highly reminiscent of the NRA in that it purports to let the big players in the health care industry help write the codes, so to speak) and the welcome declaration on Wednesday that the administration would soon seek a new regulatory apparatus for derivatives markets, Franklin Roosevelt was not the first president that came to mind as a point of reference for Obama this week.

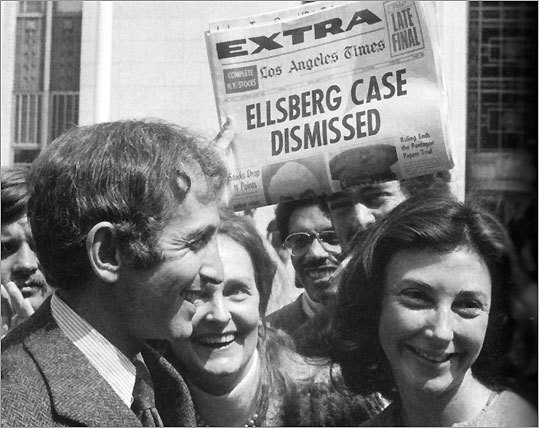

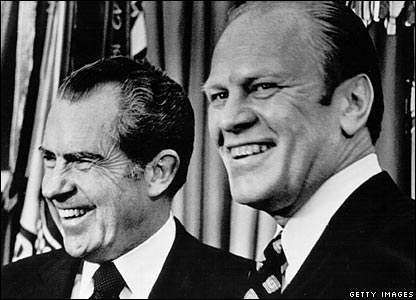

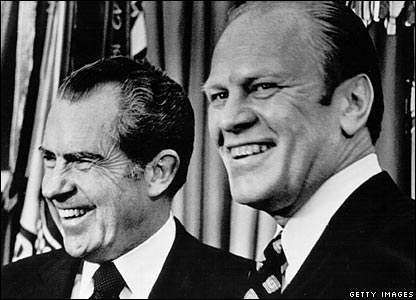

No, that would be Gerald Ford, who, most historians agree, was an honorable man thrust into a thorny dilemma by the crimes of his predecessor, and who grievously hamstrung his own brief administration by deciding to pardon Richard Nixon. And now, it seems, history gets dangerously close to repeating itself. For, it’s moved beyond obvious that the Dubya administration not only willfully engaged in torture — clearly, bad enough — but did so to compel false confessions of an Iraq-9/11 connection that they knew never existed. And yet, we’ve already witnessed the ungainly sight of President Obama equivocating on the question of prosecutions in the name of some dubious “time for reflection, not retribution.” (Never mind that, as President Obama reminds us on other matters, wounds, like corruption, fester in the dark.)

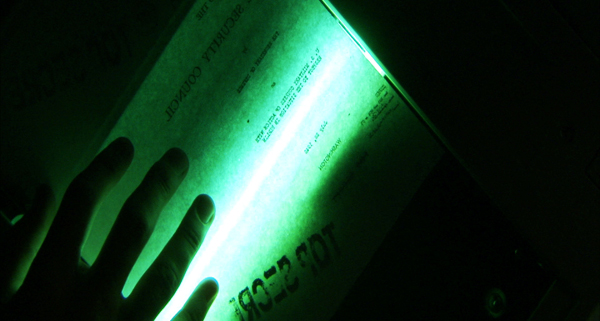

This week, President Obama has compounded his recent error — twice. In the first of two eleventh-hour reversals, Obama — who has promised us “an unprecedented level of openness in government” many times over — instead chose to side with the publicists of the Pentagon and block the court-ordered release of new photographs detailing detainee abuse: “‘The publication of these photos would not add any additional benefit to our understanding of what was carried out in the past by a small number of individuals,’ Obama said yesterday. ‘In fact, the most direct consequence of releasing them, I believe, would be to further inflame anti-American opinion and to put our troops in danger.‘” (How bad are they? If Sy Hersh is correct, and there’s no reason to think he isn’t, they could be very, very bad.)

Then, today, the Obama administration announced they will continue using extra-legal military tribunals, not federal courts or military courts martial, for Gitmo suspects. “‘Military commissions have a long tradition in the United States,’ said Obama in a statement. ‘They are appropriate for trying enemies who violate the laws of war, provided that they are properly structured and administered.’” (The key line of the WP story: “In recent weeks, however, the administration appears to have bowed to fears articulated by the Pentagon that bringing some detainees before regular courts presented enormous legal hurdles and could risk acquittals.)”

Obama’s statements aside, the arguments — re: excuses — in favor of blocking the release of these no-doubt-horrifying photos and maintaining extralegal tribunals — now with 33% less illegality! — are the thin gruel you might expect. The WP’s Dan Froomkin already eviscerated the former quite devastatingly, while Salon‘s Glenn Greenwald, laudable as usual, has taken point on the idiocy of the latter: “[W]e’ll give due process as long as we’re sure we can win, and if we can’t, we’ll give you something less.” In both cases, the principle animating the advice given to President Obama seems mainly to be the usual self-serving, CYA behavior of Dubya holdovers at the Pentagon.

But that doesn’t absolve President Obama of his failures here. For whatever reason — perhaps he’s trying to smooth things over in these areas so he can focus on the considerable domestic problems on his plate — Obama is increasingly making the exact same mistake as Gerald Ford. As other commentators have pointed out, by shoving the rampant illegalities of the GWoT under the rug — or worse, perpetuating them — Obama is dangerously close to making his administration retroactively complicit in the crimes of the previous administration.

Now, I’d like to move on to fixing the economy and universal health care — not to mention voting, lobbying, and campaign finance reform — as much as the next guy., But sidestepping the tough choices on torture and the imperial presidency, as Paul Krugman (whom I’ve had issues with but am in complete lockstep with here) noted a few weeks ago, is simply not an option, if we are to maintain anything resembling our national soul after this egregious wallowing in torture and illegality.

Speaking of which, a quick comment on the emerging question of what and when Speaker Pelosi knew about torture (which the Republicans have shamelessly latched onto like a life raft — see in particular Karl Rove frantically pointing at her to save his own skin the other day. You can almost smell the desperate flop sweat exuding from his every pore.) Well, let’s look into it. Commissions, investigations, prosecutions — let’s quit screwing around and start getting to the bottom of this fiasco. I can’t believe I have to keep writing this like it’s even a bone of contention, but look: If we can’t get it together enough to collectively agree that torture is both immoral and illegal, and that those who designed and orchestrated these war crimes during the Dubya administration be subject to investigation, prosecution, and punishment, then we might as well call this whole “rule of law” thing off. As ethicist David Luban noted yesterday in congressional testimony, the relevant case law here is not oblique. Either the laws apply to those at the very top, or they don’t — in which case, it’s hard to see why anyone else should feel bound to respect them either.

Which brings me back to pragmatism. Hey, in general, I’m all for it, particularly when you consider all the many imbecilities thrust upon the world by the blind ideological purity of the neocons of late. But, let’s remember, the limits of pragmatism as a guiding national philosophy were exposed before all the world before Obama, or even FDR, ever took office. When, after several years of trying to stay well out of the whole mess, Woodrow Wilson entered America into World War I in 1917, the very fathers of Pragmatism, most notably philosopher of education John Dewey, convinced themselves war was now the correct call and exhorted their fellow progressives, usually in the pages of The New Republic, to get behind it. (Many did, but others — such as Jane Addams and Nation editor Oswald Villard — did not.) War went from being a moral abomination to a great and necessary opportunity for national renewal. Given it was a done deal, the pragmatic thing to do now was to go with the flow.

Aghast at this 180-degree shift in the thinking of people he greatly admired, a young writer named Randolph Bourne called shenanigans on this “pragmatic” turnaround, and excoriated his former mentors for their lapse into war fervor. “It must never be forgotten that in every community it was the least liberal and least democratic elements among whom the preparedness and later the war sentiment was found,” Bourne wrote. “The intellectuals, in other words, have identified themselves with the least democratic forces in American life. They have assumed the leadership for war of those very classes whom the American democracy had been immemorially fighting. Only in a world where irony was dead could an intellectual class enter war at the head of such illiberal cohorts in the avowed cause of world-liberalism and world-democracy.“

Now, you’d be hard-pressed to find a bigger cheerleader for the progressives than I. But the fact remains that Bourne, who perished soon thereafter in the 1918 influenza epidemic, was prescient in a way that many of the leading progressive thinkers were not. The emotions unleashed by the Great War and its aftermath (as well as the sight of the accompanying Russian Revolution) soon fractured completely the progressive movement in America, and proved exceedingly fertile soil for the reascendancy of the most reactionary elements around. (Back then “Bolshevik” and “anarchist” were preferred as the favorite epithets of the “One Hundred Percent American” right-wing, although “socialist,” then as now, was also in vogue. At least then they had real socialists around, tho’.) And the pragmatic writers and thinkers of TNR, who thought they could ride the mad tiger through a “war to end all wars,” instead found their hopes and dreams chewed up and mangled beyond recognition. They wanted a “world made safe for democracy” and they ended up with the Red Scare, Warren Harding, and an interstitial peace at Versailles that lasted less than a generation.

The point being: however laudable a virtue in most circumstances, pragmatism for pragmatism’s sake can lead one into serious trouble. And, as a guiding light of national moral principle, it occasionally reeks. As Dewey and his TNR compatriots discovered to their everlasting chagrin, you can talk yourself into pretty much anything and deem it “pragmatic,” when it’s in fact just the path of least resistance. And, when your guiding philosophy of leadership is to always view intense opposing sides as Scylla and Charybdis, and then to steer through them by finding the calm, healthy middle, you can bet dollars-to-donuts that the conservative freaks of the industry will always be pushing that “center” as far right as possible, regardless of the issues involved. And, eventually, without a guiding moral imperative at work — like, I dunno, torture is illegal, immoral, and criminal, or the rule of law applies to everyone — you may discover that that middle channel is no longer in the middle at all, but has diverted strongly to the right. In which case, welcome to Gerald Ford territory.

Nobody wants that, of course. We — on the left, at least — all want to remember the Obama administration not as a well-meaning dupe notable mainly for its unfortunate rubberstamping of Dubya-era atrocities, but as a transformational presidency akin to those of Lincoln and the two Roosevelts. To accomplish this goal, it would behoove the White House to remember that Lincoln, pragmatic that he was, came to abolition gradually, but come to abolition he did. Or consider that Franklin Roosevelt, pragmatic that he was, eventually chose his side as well. “I should like to have it said of my first Administration that in it the forces of selfishness and of lust for power met their match,” FDR said in his renomination speech of 1936. “I should like to have it said of my second Administration that in it these forces met their master.”

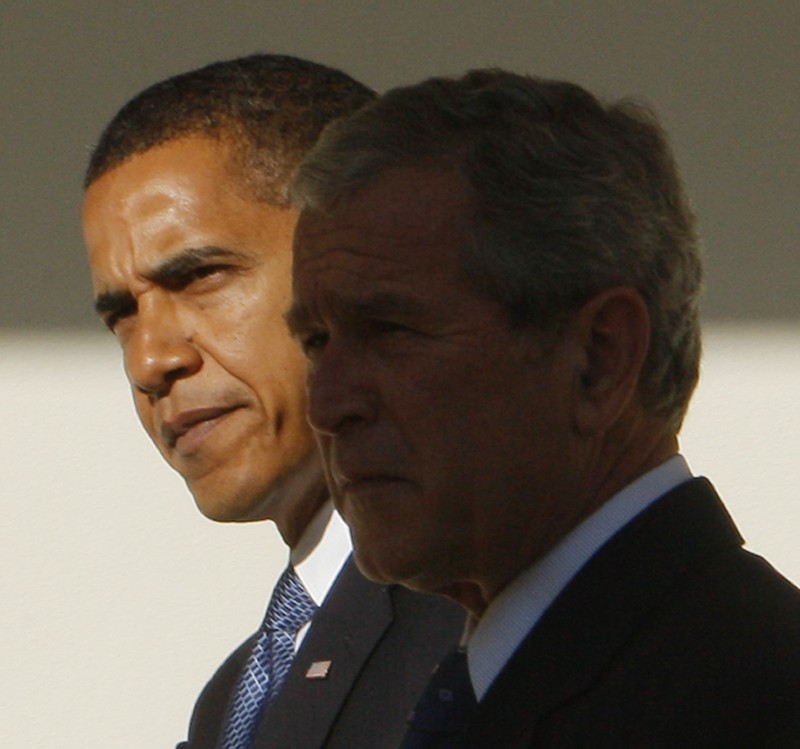

I should like to have it said of President Obama’s administration as well. The alternative — Obama’s sad, “pragmatic” capitulation to Dubya-era criminals — is too depressing to contemplate. But the picture below (found here) gives you a pretty good sense of what it’ll mean for America if we don’t get to the bottom of this, and soon.