As gripping in its own way as a cloak-and-dagger thriller or John Grisham procedural,

Daniel Ellsberg: The Most Dangerous Man in America, by co-directors Judith Erlich and Rick Goldsmith and about the

famous Rand analyst turned Pentagon Papers whistleblower, is a smart, tautly-made conjuring of recent American history that’s well worth the trip. And, fortunately for me, it’s also a perfect movie to contemplate and write about this

President’s Day.

On one hand, the film makes for an interesting moral counterpoint to The Fog of War: Ellsberg’s actions put the lie to a lot of McNamara’s convenient post-hoc rationalizing therein — clearly, SecDef could’ve done more at the time to end the war in Vietnam.) On the other, Ellsberg also works as a prequel of sorts to All the President’s Men — to say nothing of a generation of seventies paranoia epics like The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor. But in the end, The Most Dangerous Man in America probably works best as an eloquent testament to the words of the late Howard Zinn (who appears here as an old friend of Ellsberg): “Dissent is the highest form of patriotism.”

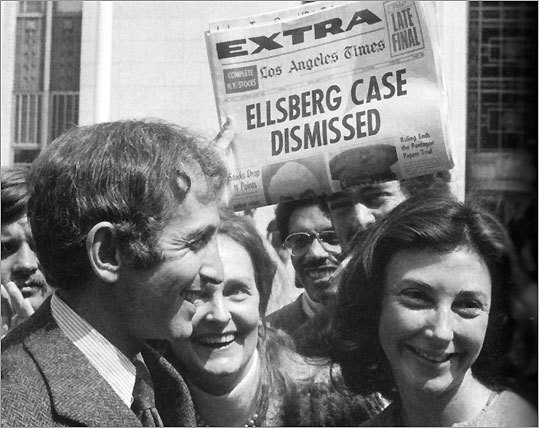

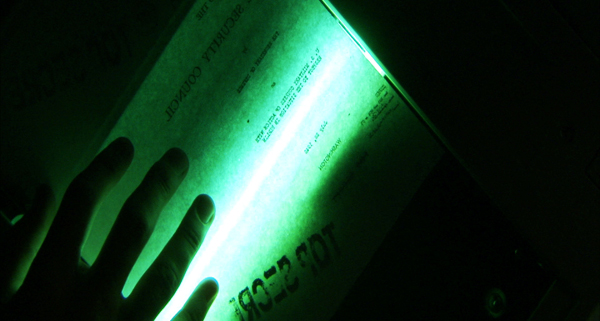

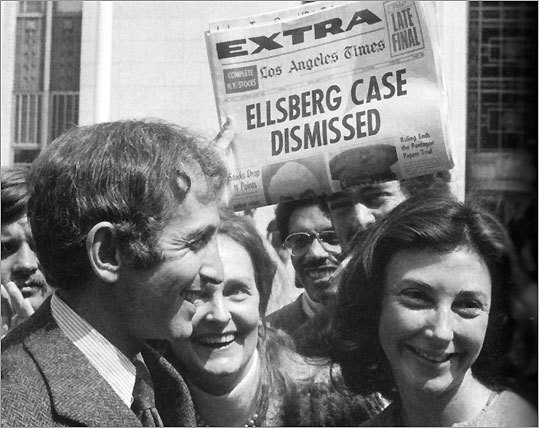

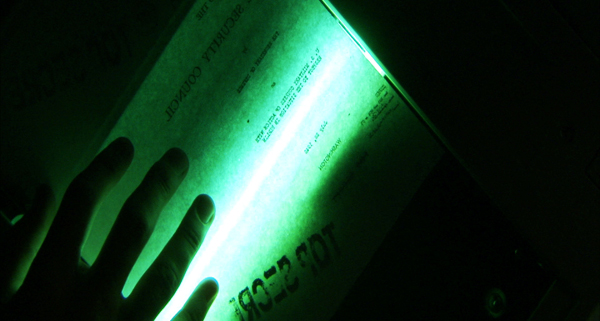

Like Man on Wire, Ellsberg starts here in media res, and at the scene of the history-making crime. Furtive eyes scan back and forth as an old-school Xerox copier whirrs in the dark, its green light illuminating maps of Southeast Asia and the ominous words “Top Secret” from below. With no zip drives or electronic files to speak of, analyst Daniel Ellsberg is forced to copy the 7000 pages of the Pentagon Papers page by painstaking page. It’ll take months (and eventually he enlists the aid of his kids.) As the Xerox churns, we get up-to-date on the ramifications of the document being processed — bombs fall from the sky over North Vietnam and Cambodia, weary troops patrol the hot, fetid jungle, and Nixon and Kissinger obsess over the leaks in their war machine (with Kissinger giving Ellsberg his moniker: “the most dangerous man in America.”)

Cut back to several years earlier, when the future leaker of the Pentagon Papers seemed quite a different man indeed. A fresh-faced young ex-Marine with a crisp, no-nonsense Kennedy era haircut, Ellsberg began his tenure in government as one of the Best and the Brightest, with an enthusiasm for his 80-hour workweek matched only by his hawkishness. As one of McNamara’s boys, Ellsberg concedes to helping massage the data to create a casus belli for the war. His first day on the job is the Gulf of Tonkin incident that wasn’t, and he spends subsequent weeks trying to dredge up some, any, horrible atrocities in the region that might involve Americans.

But, over time, the scales fall away from Ellsberg’s eyes. In part because he makes the acquaintance of a luminous lefty-leaning journalist named Patricia, who eventually becomes his fiancee…twice. (Ellsberg has a great line about a guy he meets at a peace rally who’s a Trotskyist. He asks this fellow how in Hell he ever became a Trotskyist. The answer: “The same way anybody becomes anything. I met a girl.”) And in part because, driven with an analyst’s overriding compulsion to find the right answer, he starts going to Vietnam himself to lead recon missions on the side and get a better sense of the situation on the ground. Simply put, the Ground Game is not going well.

The rest, as they say, is history. Moved to throw a shoe into the gears of the war machine he had helped nurture into existence, Ellsberg goes rogue and decides to publish the top-secret history of the war. But, even if you feel like you know the story of the Pentagon Papers pretty well, and I thought I did, there are some fresh and intriguing insights here. For example, I’m not really one for Freudianism or overthinking coincidences, but it turns out Ellsberg suffered a tragedy at the age of 15 that made him uniquely primed to play the role in history he ended up playing. (His father fell asleep at the wheel during a road trip, prompting a crash that sheared the car in two and killed Ellsberg’s mother and sister. In other words, watch the authority figures at the wheel verrry carefully.)

And then there’s the man himself, who’s an engaging presence throughout (if perhaps with a touch of monomania — I could see him being a hard guy to get along with.) If The Most Dangerous Man in America has a flaw, it’s that the movie is quite one-sided in the end — Ellsberg even narrates much of the story, and you get the sense at various points there may well be some whitewash being applied. (Ellsberg has an ex-wife, and kids, that aren’t even mentioned for the first 45 minutes or so.) Still, I’m inclined to give Ellsberg — and Ellsberg — the benefit of the doubt (and not just because the man loves his movies.) Ever since George and the cherry tree, we’ve been smoothing the edges of our patriotic tales. And, whatever his misdeeds as a man, Daniel Ellsberg, the film makes clear, is a patriot, through and through.

I use this Cornel West quote rather often, but that doesn’t make it any less true: “To understand your country, you must love it. To love it, you must, in a sense, accept it. To accept it as how it is, however is to betray it. To accept your country without betraying it, you must love it for that in it which shows what it might become. America – this monument to the genius of ordinary men and women, this place where hope becomes capacity, this long, halting turn of the no into the yes, needs citizens who love it enough to reimagine and remake it.”

Daniel Ellsberg is one of those citizens. He saw an obvious crime being perpetrated by our government across multiple presidencies, and he did his part to help put a stop to it. In many ways, the story told in The Most Dangerous Man in America seems quaint: Johnson actually asked Congress for authority to bomb Vietnam? The press wasn’t rolling over like a lapdog in the wake of obvious propagandistic lies? (In fact, the media types who show up late in Ellsberg clearly possess some of the narcisstic sense of self-entitlement that has been our undoing of late. Ellsberg the civilian sweats blood and tears to get this 7,000-page document out in public, and the press poobahs act like they’re both the knowing gatekeepers and the heroes of the story.)

But just because Ellsberg’s brand of patriotism has fallen out of fashion in the era of Judith Miller and the chattering class doesn’t make this story any less relevant. It makes it more relevant. If we’re going to keep our young republic through its third century, we need more men and women of Ellsberg’s stripe. Men and women who will buck the trend, risk the ridicule and wrath of their well-connected peers, and stand up against injustice done under our collective name when they are party to it.

Presidents will get their due on this and every subsequent Presidents Day to come. But, now and again, it’s good to honor those patriots who, through non-violent principle and sheer, dogged determination, help to keep our leaders in check when the separation of powers fails — ordinary folks like you, me, and Daniel and Patricia Elllsberg.